International Railway Journal: Andrew Goltz about Polish InterCity

On 14 December 2014, Poland’s long distance passenger train operating company, PKP InterCity, launched its brand new service Express InterCity Premium using seven-car Class ED250 Alstom-built trainsets, and just one month later said goodbye to to its CEO Marcin Celejewski. In fact, Celejewski departure from the helm of IC had been on the cards for some time as he had failed in his main task of delivering cheap airline style demand-related pricing and had been unable to stem the haemorrhaging of passengers.

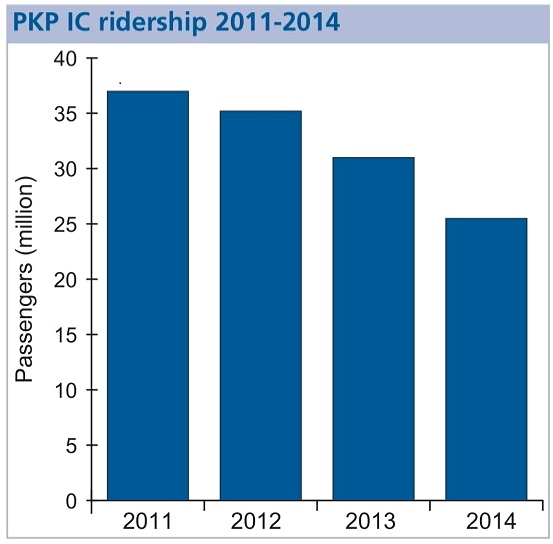

PKP IC carried 30.7 million passengers in 2013, but only some 25.5 million in 2014, a loss approximately of 5.2 million passengers (-17%). Most of the passengers deserting PKP IC were those who used the company’s services for relatively shorter journeys, as the decline in passenger kilometres (from 7,085 million in 2013 to 6,221 million in 2014) was a more modest -7.9%.

While PKP IC has yet to publish its 2014 financial results, a quick ‛back of the envelope’ calculation shows the magnitude of the disaster. In 2013, PKP IC declared an overall loss of 87.2 million PLN, on a difference between sales revenue and operating expenses of 91.3 million PLN. Adjusting sales revenue in accordance with the 8% reduction in passenger km in 2014, and assuming that any savings achieved in operating expenses was cancelled out by increased debt service charges, the gap between sales revenue and operating revenue opens out to a huge 282.6 million PLN.

On initial consideration, it would seem Celejewski’ s successor, PKP SA privatisation guru, 33-year old Jacek Leonkiewicz, should find his period at IC less of an uphill task than his predecessors (over the last 10 years there have been 9 chairmen!) Track has been upgraded, speed limits removed, and new or refurbished rolling stock introduced. In step with all these investments, IC is repositioning itself upmarket as competition to the domestic cost airlines, rather than to the cheap and cheerful bus services run by Adrian Shooter’s new company PolskiBus.

So will the strategy work? PKP insiders, as well as external rail pundits, that I have spoken to have their doubts. Many Poles see themselves and their country as still trying to catch up after 60 lost years (1939 – start of WWII to 1989 – the end of communism and Soviet hegemony in Poland). Owning, and using, a car at every available opportunity is seen as part of that catching up process. With the exception of long-distance commuters and bargain hunting holidaymakers, Poles who have a choice, prefer travelling car.

For a PKP to market its Pendolino trains as a premium service, the whole journey – door to door – needs to be seen as a ‛premium’ experience, not just the rail portion. However, the other elements of the journey: taxis, buses and trams, are regarded as very much ‛second class’ transport, while most station lack safe, secure and convenient parking places. Here we have the nub of the matter, as the decision to focus on the higher premium market, stems not from careful market analysis, but rather is forced on PKP IC by high track access charges. This is a fundamental problem for all Polish train operators. The Polish government sees little need to subsidise Poland’s railway track, and encourages infrastructure manager, PKP TLK to adopt a ‛what the market will bear approach’ when setting charges.

So what about the remaining long-distance services operate by PKP IC under the TLK brand,non-tilting Pendolino originally Tanie Linie Kolejowe (Cheap Railway Lines), but now Twoje Linie Kolejowe (Your Railway Lines)? Here, because much of Poland’s secondary trunk rail network remains in an appalling state, journey times and ticket prices are uncompetitive on routes served by PolskiBus. A negative feedback spiral is in progress – passengers are leaving the railway in droves, services are cut back and more passengers desert the remaining services.

So what should Leonkiewicz be doing to reverse the flow of desertions from PKP IC? Here are six priority areas which require his urgent attention:

1. Re-focusing the company on the customer. Too many people in PKP IC are still focussed on the trains. There has been progress of sorts. Customer-facing staff have been sent on ‛customer satisfaction’ courses. Train managers have become more polite, and have even been known to stop departing trains so that last minute stragglers can board. But senior people have yet to realise that true customer focus must start at the very top of an organisation. When things go badly wrong (such as a broken down or cancelled train) staff need to be empowered to deal with such problems on the spot, by granting them power to revalidate old tickets, or issue new replacement tickets, without having to charge the customer a second time. An enormous amount of anger will be saved, and goodwill generated, by such a simple step. When things do go wrong, one of the worst things that can happen to a passenger is to be told by the train manager that a brand new ticket must be purchased, and that a refund for the old ticket can only be obtained via a bureaucratic complaints system.

2. Improving internal communications, Most of the PKP group’s internal culture is still firmly rooted in ‘Command and Control’ mode, a left over from the days when Poland’s railways were an integral part of the Warsaw Pact’s military machine. Senior directors feel more at home attending Powerpoint presentations from consultants, than talking – and listening – to their employees. Instigating a ‘reverse channel’ so information can flow upwards from staff to their managers, regional directors and main board members should be one of the top priorities.

3. Commissioning a brand new ticketing system. In spite of PKP IC’s attempt to introduce low-cost airline style discount pricing, the ticketing system is still a shambles. Just one example: passengers needing to change trains have to buy separate tickets for each train (thus loosing the through journey discount) when purchasing their tickets through the Internet.

4. Improving the customer experience at stations. In the last few years major stations have undergone complete rebuilds or makeovers – a process partly accelerated by Euro 2012 championship (though relatively few football fans actually travelled around Poland by rail). But too many stations lack decent waiting rooms with comfortable seats; train destination boards display incomplete information on destination boards; decent restaurants and bars are conspicuous by the absence.

5. Improving routes for less-abled passengers. To give credit where credit is due, major stations around the PKP network are being fitted out with escalators and/or lifts. But architects are failing to provide integrated solutions – complete routes that can easily be navigated without encountering a flight of steps. One can, for a time at least, excuse such problems at legacy buildings like Warszawa Centralna, but for newly delivered projects, such as the new passenger facilities at Kraków Główny, this is inexcusable!

6. Enthusing staff and passengers with the ideal of safe, ecologically sound, rail transport. Rail travel was once seen as the premium travel mode; in many parts of Europe it is being viewed as such again. PKP IC should be involving its passengers and staff in a campaign to promote the benefits of safe, ecologically sound, rail transport!

Will Lenkiewicz have the courage to tackle PKP InterCity’s internal problems head on, or will he see his main priority as quickly getting the company in better financial shape for privatisation and making deep cuts in TLK’s loss-making services? Whatever business strategy he adopts, with parliamentary elections due in November this year, he may – like his predecessors before him – have very little time to make his mark.